The rapid advancement of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has ushered in a new era of digital risks. Among the most concerning is the creation and dissemination of AI-generated child sexual abuse material (AI CSAM).

As the boundary between real and synthetic content collapses, offenders are increasingly using AI tools to bypass traditional barriers to creating and sharing abusive material. This presents new and profound challenges for lawmakers, law enforcement, and tech companies alike.

This blog explores the rise of AI-generated CSAM through the lenses of technology, psychology, and law — and why coordinated action across research, regulation, and platform governance is urgently needed to confront it.

From fantasy to felony

AI CSAM can include manipulated content, where real child imagery is digitally altered, or fully synthetic content, where AI models generate child abuse imagery from scratch. Both formats are proliferating, and both are illegal under UK and EU law, regardless of whether a real child was physically abused in the image’s creation.

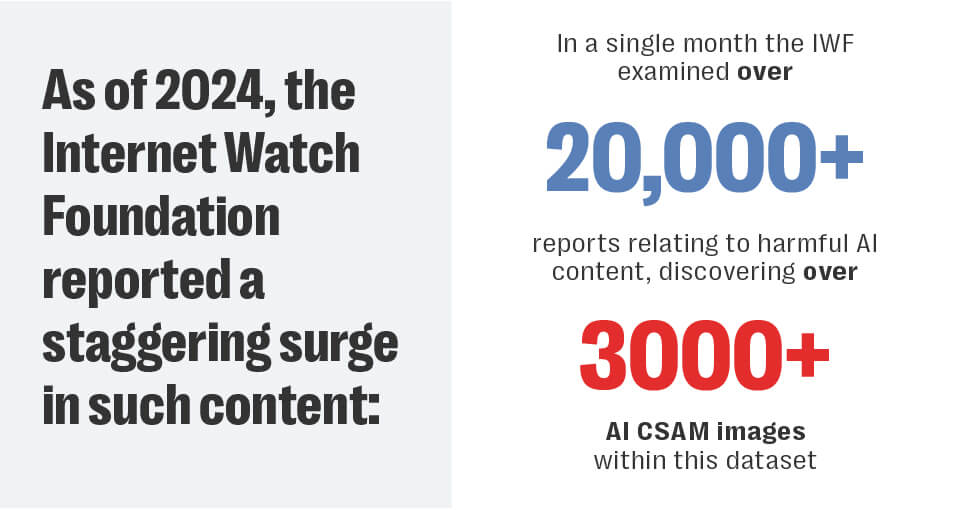

As of 2024, the Internet Watch Foundation reported a staggering surge in such content, identifying over 3,000 AI-generated CSAM images in a single month.

Offenders no longer require technical sophistication. Forums provide detailed guides, open-source models, and even community mentorship — creating a disturbing culture in which perpetrators self-identify as “artists,” thereby attempting to morally dissociate from their actions.

What was once prevalent predominantly in the dark web is now bleeding into the clear web, indicating both market demand and widespread access to generative tools.

The mind and marketplace for offenders

The growing accessibility of generative models reduces the psychological and logistical friction of CSAM offending. Unlike traditional Indecent Images Of Children (IIOC) acquisition, AI CSAM does not require contact with a child, grooming, or high-risk digital behavior.

Researchers believe that this reduced barrier lowers the perceived criminality of engagement. In this manner the “synthetic” nature of the material helps those committing such crimes justify their behaviors and mitigate feelings of guilt or responsibility for their actions.

Yet the psychological and societal harm remains profound. AI-manipulated content typically involves real children’s images, while synthetic content still reinforces exploitative fantasies that can escalate toward real-world abuse.

Economically, synthetic CSAM has found its niche within dark web marketplaces. Although much of the content is shared freely, research into criminal motivation on the dark web estimates that up to 31% of dark web platforms trade in synthetic IIOC – illustrating its commercial viability.

A comparative analysis of global legal frameworks

The legislative response to AI CSAM has been robust in rhetoric, but inconsistent in implementation.

United Kingdom

At present, the United Kingdom does not have AI-specific criminal legislation targeting AI-generated Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM), but existing laws have been adapted to treat AI-generated CSAM with the same seriousness as traditional (real) CSAM.

The UK has taken a leading stance through the Online Safety Act (2023), criminalizing both synthetic CSAM and the distribution of associated “manuals.” Previous legislation such as the Protection of Children Act (1978) and Coroners and Justice Act (2009) already encompass pseudo-images and obscene non-photographic content.

However, at this point in time, there are no explicit laws governing the development or possession of AI models used in the creation of CSAM, nor are manuals for generating synthetic content categorically banned unless used in connection with abuse – though this is under policy review. Proposed changes will involve the creation of a new offence, making it illegal to adapt, possess, supply or offer to supply a CSAM image generator, punishable by a maximum sentence of five years in prison.

Additionally, CSAM will be defined in accordance with existing legislation, i.e. photographs/pseudo photographs (section 1 of the Protection of Children Act 1978) or prohibited images (section 62 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009). Under Section 69 of the Serious Crime Act 2015, it is an offence to possess any material that offers instructions or guidance on how to sexually abuse children—commonly referred to as “paedophile manuals.”

However, the scope of this offence specifically relates to acts defined under Section 1 of the Protection of Children Act 1978, and notably excludes pseudo-photographs from its remit. A pseudo-photograph is any image, including those created with computer graphics, that gives the impression of being a real photograph. As a result, AI-generated images — if they appear photorealistic — would typically fall into this category and thus would not be liable under Section 69 of the 2015 Act.

European Union

The Digital Services Act (DSA) (2024) holds platforms accountable for removing all forms of illegal content, including AI-generated CSAM. Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) must assess and mitigate systemic risks posed by generative AI misuse and provide transparent reporting. However, enforcement varies widely across member states, and the scope remains primarily reactive.

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), formally adopted in 2024 and due to be fully enforced by 2026, represents the most comprehensive attempt yet to regulate AI systems across a broad spectrum of use cases. Although the legislation does not explicitly target the creation or distribution of Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM), it is poised to influence how such content is produced and moderated when AI is involved. This influence stems from the AI Act’s risk-based framework, its obligations on general-purpose AI systems, and its alignment with other digital regulations like the DSA.

The AI Act also dovetails with the DSA, which regulates how online platforms detect, report, and remove illegal content. When applied together, the two frameworks establish a dual line of responsibility: the AI Act governs the creation and architecture of AI systems, while the DSA ensures that online intermediaries—including social media companies, hosting services, and marketplaces — are actively moderating their ecosystems.

United States

The “Take It Down Act” criminalizes the sharing of intimate images without consent, including those created using AI, and requires online platforms to remove such material within 48 hours of notification from the victim. It aims to provide victims of non-consensual intimate images with protections and a streamlined process to remove the harmful content.

The act makes it a federal crime to knowingly publish or threaten to publish intimate images without consent, including those created using AI like “deepfakes”. Online platforms (e.g., social media, websites) are required to remove the non-consensual intimate images within 48 hours after a victim requests it.

The act aims to protect victims of non-consensual sharing of sexual images by providing them with a clear process to have the content removed and holding platforms accountable. The act applies to public-facing platforms, meaning it doesn’t address private, encrypted, or decentralized networks where such abuse may occur. Online platforms have a one-year period (until May 19, 2026) to establish compliant reporting and removal procedures.

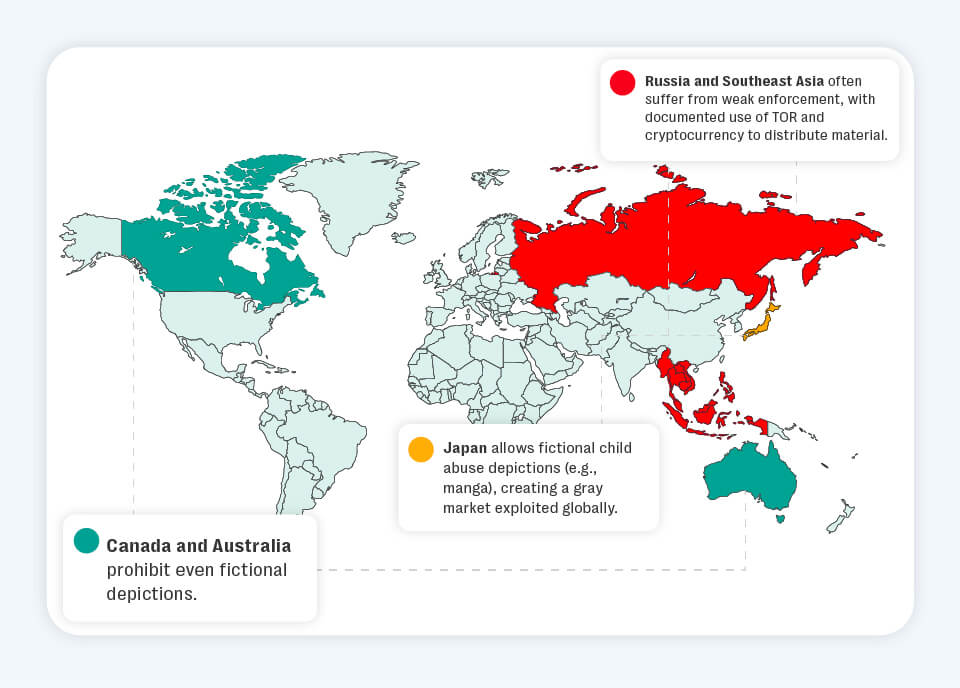

In contrast to the UK and the EU, jurisdictions like Japan and parts of the United States have more ambiguous positions. In Japan, fictional representations (e.g., manga or anime) involving minors are legal if no real child was used. In the U.S., obscenity laws and the PROTECT Act (Senate Bill 151) apply, but courts may vary in interpreting whether AI-generated depictions meet the threshold.

This legal inconsistency creates enforcement challenges. However, it does not relieve platforms of responsibility. Increasingly, companies are judged not just by what is legal, but by what is responsible.

Internationally, there is growing recognition that the intent behind content—whether AI-generated or real—is equally harmful. Still, technological agility continues to outpace legal reform.

Gray areas and policy gaps

One of the thorniest issues for T&S teams is content that sits in legal gray areas. For instance, text-based grooming scenarios generated via large language models may not clearly violate existing child protection laws, yet their purpose and impact are deeply problematic.

Similarly, anime-style sexualised illustrations of childlike characters may be lawful in some regions but could constitute prohibited content in others. Without a real-world victim, enforcement is murky, but the content still contributes to the sexualisation of minors and the normalisation of abuse.

Many platforms still rely heavily on hash-matching and keyword detection to identify CSAM. These methods are ineffective against novel, AI-generated content. In some cases, moderation teams may lack the contextual or cultural knowledge to understand when seemingly fictional content is grooming-adjacent or exploitative.

Another significant challenge for platforms is balancing harm prevention with freedom of expression. Fictional content occupies a contested space in many legal systems, and there is concern about overreach or censorship.

However, the guiding principle should be that fiction that facilitates real-world harm is not harmless. Whether it is a grooming script, a photorealistic child avatar in a sexual context, or a story glorifying abuse, these materials contribute to a broader ecosystem of exploitation.

Trust & Safety teams are not courts, but they are stewards of platform integrity. Their goal is not only to comply with the law, but to uphold environments where harm is minimised, dignity is preserved, and abuse is neither encouraged nor normalised.

Why AI CSAM evades detection systems

Current detection systems like PhotoDNA rely on hash-matching against known abuse imagery. AI-generated CSAM, by its nature, creates novel content each time—rendering these tools largely ineffective.

Compounding this challenge is the ethical dilemma of training AI moderation models on synthetic CSAM data: doing so would require creating or maintaining access to harmful content, even for research purposes.

Moreover, human moderation is similarly limited. GANs and diffusion models can produce imagery indistinguishable from real photos, and platform moderators often struggle to interpret the context or legality of content presented as “fiction” or “art.”

Without updated detection systems, moderators face an impossible task: distinguishing illegal synthetic content in an ethical, scalable, and legally compliant manner.

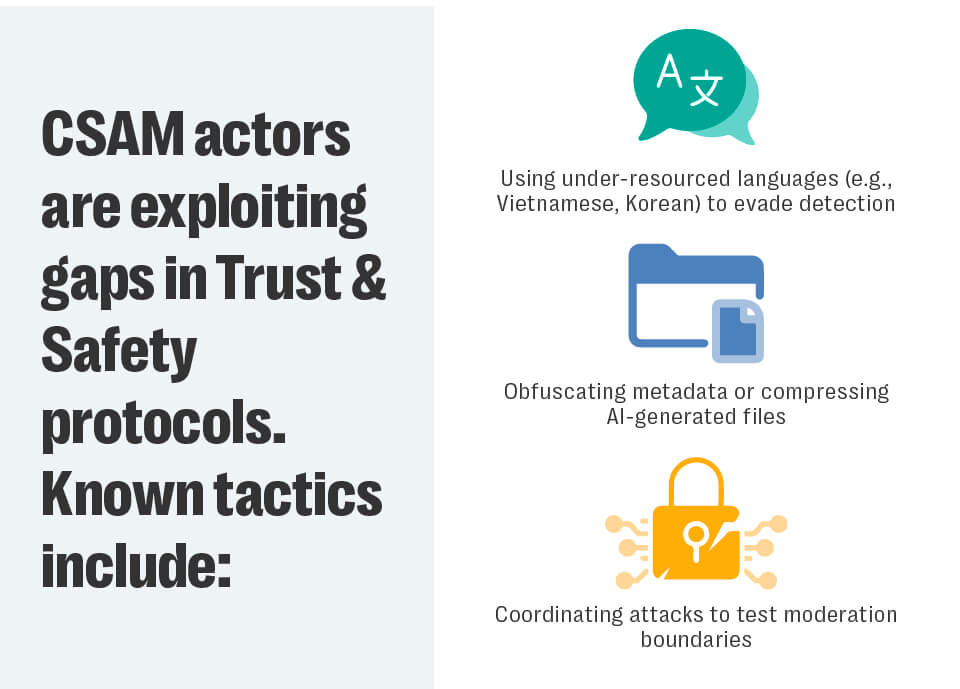

These behaviors reveal not only the sophistication of offender networks but also the vulnerabilities of platform architecture. Moderation strategies designed for legacy CSAM are fundamentally ill-equipped to manage the dynamic, evolving nature of AI abuse content.

T&S Intelligence in action – Industry recommendations

To prevent further entrenchment of AI CSAM networks, stakeholders must act decisively. Recommendations include:

- Expand Definitions of Harm: Platform terms of service must explicitly prohibit AI-generated depictions of abuse, even in fictional contexts.

- Integrate AI Governance into Moderation: Content generation tools must include safety filters, prompt flagging, and usage logging. Developers should be held accountable when tools are misused at scale.

- Build Innovative Detection Models: Embrace next-generation detection tools that capture AI generated and other ‘novel’ content’.

- Advocate for Legislative Clarity: Governments must close loopholes around nudification software, CSAM training guides, and AI model liability.

- Support Cross-Sector Collaboration: Join coalitions such as INHOPE, WeProtect, or the Tech Coalition to share intelligence and best practices across jurisdictions.

Recommendations for Trust & Safety Teams

To address synthetic CSAM and associated harms effectively, platforms need to go beyond traditional moderation models. Here are key recommendations:

| Define and Prohibit Pseudo-CSAM in Community Guidelines: Terms of service should explicitly state that AI-generated sexual depictions of minors, grooming manuals, and nudified images violate platform rules. Policies must evolve alongside technology. | |

|

Implement AI-Specific Detection Tools: Invest in tools capable of identifying synthetic content, including perceptual hashing for deepfakes, context-aware LLM monitoring, and nudification detection.

|

|

| Train Moderators on Contextual and Cultural Cues: Moderators must be equipped to recognise culturally specific euphemisms, anime or cartoon representations, and grey-area grooming language. Human-in-the-loop systems can help make nuanced decisions. | |

| Proactively Monitor Emerging Threats: Proactively seek intelligence related to malicious on-platform actors, dark web forums, niche image generators, and prompt-sharing communities to anticipate misuse. Offender communities often innovate faster than platforms can react. | |

| Engage with Regulators and NGOs: Work closely with organisations like INHOPE, WeProtect, and NCMEC to develop classification frameworks and improve cross-jurisdictional consistency in how synthetic abuse is reported and removed. | |

| Address Open-Source Risks : Where possible, discourage or limit the deployment of open-source models known to generate high volumes of synthetic CSAM. Apply watermarking or prompt filters to mitigate misuse. |

How Resolver helps platforms to achieve these goals

The proliferation of AI-generated CSAM presents a dynamic challenge that outpaces traditional, automated moderation systems. The core issue is not merely technological; it is the human element driving the abuse. Offender networks innovate faster than platforms can react, exploiting legal gray areas, under-resourced languages, and cultural nuances to evade detection.

Resolver’s Human Intelligence-led and technology supported approach to supporting platforms, frontline services, NGOs and policy development is unique. Our Subject Matter Experts provide vital in-depth insight into online harms through decades of professional experience in Trust and Safety, Law Enforcement and Academia.

Our specialized Trust & Safety Intelligence service enables platforms and technology service providers to proactively anticipate threats, close policy gaps and protect their online communities. To learn more about how your platform can move beyond reactive moderation and build a robust child safety strategy please reach out.